Official IWW News at Industrial Worker

Launched in 1907, Industrial Worker is the official English-language publication of the Industrial Workers of the World, a worker-led union dedicated to direct action, workplace democracy and industrial unionism.

The Organizer and the Disorganized Resistance

Last year, my workplace instituted a number of changes to our time off policies. While a couple of these changes were good, most ranged from annoying to very bad. We lost most of our ability to take paid sick time (down to the legally mandated 5 days) and were informed that any vacation time we had at the end of the year would be lost without being paid out (previously it would roll over). While the company tried to spin the changes, most people recognized what was happening: things were getting worse.

Anticipating this, our bosses had human resources put on two virtual presentations to explain the changes for any of us who might be confused. Neither had time for questions, suggesting that HR understood exactly what was happening. The first presentation, however, had dozens of workers expressing displeasure through the chat feature. One worker said, “now we know why there is no time for questions,” and another even said, “we should keep making a fuss.” In the second presentation (which had the same content), HR disabled the chat. The changes continued to be a topic of discussion throughout unit meetings and among co-workers, and slowly management began rolling back some changes. First, they announced that workers who lost a vacation day due to the new method for calculating days would get a bonus vacation day the following year (meaning there would be no net loss for anyone), then it was announced that up to one day of vacation could be paid out if not taken, then finally that any unused vacation time would be paid out at the end of the year.

Throughout this time, I had begun talking with my co-workers about the changes, as any good Wobbly would, and a few of us had started a small organizing committee. This makes it tempting to count the changes our bosses rolled out as wins. Are they, though? After all, most of the people complaining hadn’t spoken to a committee member before doing so.

Before we answer that question, I want to contrast this with another worker in a similar situation in a similar workplace. Their summary follows:

A few years ago, my employer changed the supplier for the prescription drug insurance benefit offered to salaried employees located in the United States. As a result of this change, employees were abruptly forced to transfer their prescriptions from their pharmacy of choice to either Walgreens or a mail order service, and they were restricted to filling long-term maintenance prescriptions in 90-day quantities. This was communicated poorly, with vague language emphasizing that the change was giving employees the power to choose (between picking prescriptions up from Walgreens in-person and having prescriptions delivered by mail) and suggesting that employees could save money by transferring their prescriptions to Walgreens (rather than clearly and explicitly stating outside of fine print that employees would not be able to get prescriptions covered at other pharmacies). In addition to these changes, the list of covered medications changed, resulting in a number of employees losing coverage for expensive prescriptions. Overall, the impression was very much that the prescription insurance benefit became substantially worse.

Employees who had been negatively impacted by the change in benefit provider began to discuss their experiences with each other through a variety of internal channels of communication. As one of those employees, I was involved in a number of these discussions, but they were only that—discussions among employees with no clear plan for action. At around the same time, I was also getting involved in a very small organizing campaign, and I wanted to do something about the change in benefits, but I knew that we did not have nearly the numbers that would be needed to publicly take direct action as a union. Instead, I worked with some contacts from a corporate employee group to collect emotionally impactful stories about the negative consequences of the change and feed them to a sympathetic employee in HR. Eventually, the company worked with the new prescription benefit provider to allow employees to once again utilize a pharmacy of their choice. This was a win, but it was a small one, and while I believe that we collectively influenced the company’s decision to make a change, it wasn’t something for which our campaign could take credit. I wasn’t able to talk openly with everyone involved about organizing, which was unfortunate. Still, given the size of our campaign, I think that avoiding public action was the correct choice.

While our win was small, I have been able to use some of the conversations sparked by this issue as springboards to bigger conversations around organizing. I have since had one-on-one conversations with a couple of fellow workers who were impacted by this issue, and one has joined our campaign. For me, the whole experience shows that there is value in taking even small actions, that even a small number of workers can make a difference through direct action, and that paying attention to the concerns of fellow workers pays off.

First of all, we should note that a union is multiple workers acting together to make changes in the workplace. However, a union that seeks to endure as an organization cannot be a group of workers that takes collective action once. From this perspective, while what we did was union activity, it reflected a response to existing discontent rather than stemming from our organizing. Looking at my fellow worker’s actions in their campaign, I want to draw a few contrasts and lessons.

First, by collecting stories and identifying a channel by which HR could be pressured, the organizer was able to increase the pressure on management to fix the problem. This shows how knowledge of how to formulate and conduct good direct action can be applied even if other workers aren’t familiar with what you’re trying to do. Second, by using the experience in further organizing conversations, organizers can easily demonstrate to our co-workers how even loosely coordinated action can have some effect. Identifying imperfect examples of collective action in our workplace can be more impactful to our co-workers than more perfect examples from elsewhere (although I think both types of stories have value).

Some organizers, in encouraging greater militancy, have said that “union is a verb.” This is true, but union is also a noun. The union is workers acting together, but it is also the organization that exists between actions. To the extent that workers engage in union action without a union organization, we should expect to see things we wouldn’t recommend, such as individuals singling themselves out or communicating their displeasure or even desire to organize in public. We should encourage organizing best practices when we can safely and covertly do so, and we should also use the action to try to build the union as an organization. For example, in identifying the right target for the action (such as a specific person in HR) and suggesting delivering the demand in a way that maximizes emotional pressure in a short period of time, we can make demands more likely to be met. By later reminding other workers of the action and emphasizing its collective nature, we can help workers see the power of collective action. After all, if one mostly unplanned, loosely collective action gets some changes, it’s no great leap to realize that planning more collective actions is a way to get more changes.

-Daniel Bovard-Katz and Margaret Ignatowski

Originally published on Industrial Worker.

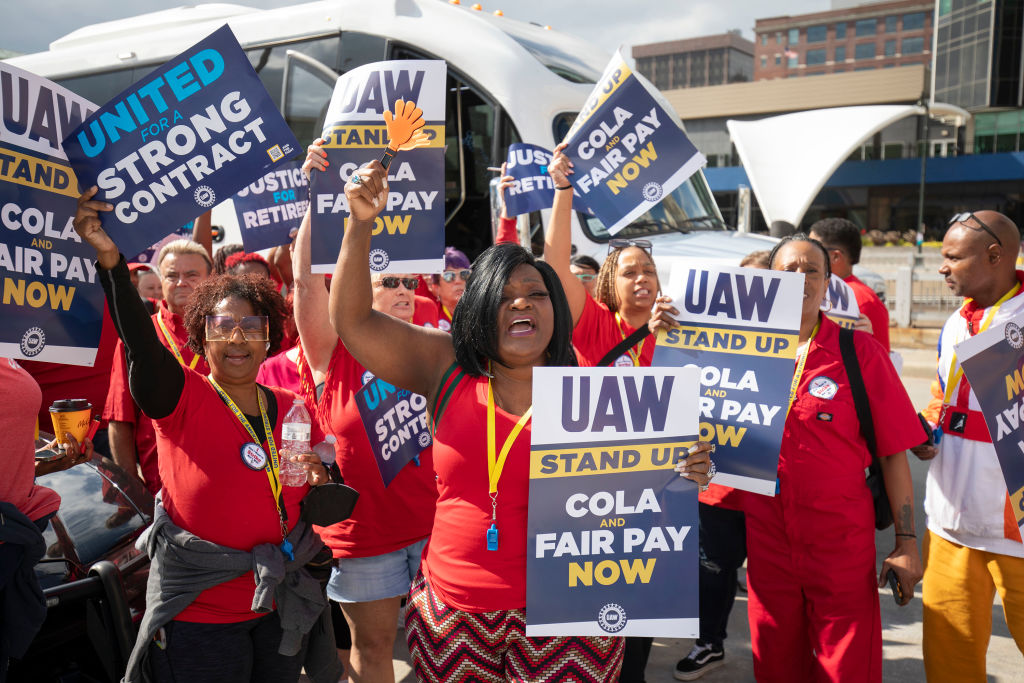

United Auto Workers on Strike

United Auto Workers members at a rally in Detroit, Michigan on September 15, 2023. The UAW is striking all of the Big Three auto makers at the same time for the first time in history to make demands on the bosses! (Photo by Bill Pugliano/Getty Images)

The UAW is conducting a coordinated strike against the big three.

DETROIT, MI — It’s September 15. I’m stuck in traffic on my way to the UAW rally. Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT), Rashida Talib, UAW President Shawn Fain and others will be speaking. There are state police on the road, more than usual. I’m stuck in traffic for 15 minutes–then stuck downtown for another thirty. I miss half of the speakers.

Workers at 3 UAW plants are on strike for a 36 percent four-year pay raise, cost-of-living adjustments, a 32-hour week with 40-hour pay, an end to the tier system, returning their defined-benefit pensions for new hires, and pension increases for workers who have retired. Many of their demands were benefits they previously received before being clawed back by the company and union officials in their 2007 union contract, allegedly due to the recession. The workers are on strike at the GM Plant in Wentzville, Missouri, a Ford plant in Wayne, Michigan, and a Stellantis plant in Toledo, Ohio. (Stellantis owns Jeep and Chrysler). Their demands track with other strikes occurring around the county, especially for cost-of-living adjustments. It seems that their strategy will be a staggered strike. UAW president Shawn Fain warns that “many more factories may follow.” In total 146,000 workers have walked off the job, and they are feeling fired up.

The UAW is holding the rally outside of the UAW-Ford National Program Center, just under the people mover, Detroit’s raised rail that goes to a few places downtown. It rumbles above, a backdrop to the fiery speeches being delivered.

Many of the workers are afraid of plant closures. As our manufacturing capacity shifts to renewables, many are afraid that without proper retraining programs, these workers will be out of a job. As for the electric manufacturers that do exist, these factories are nonunion, low-wage jobs.

We march down Jefferson to Beaubien St. I’m in a loose formation behind a banner, and there is a crier behind me. She chants “No justice! No jeeps!” We stop at Beaubien to rally and clump together before heading back up towards the program center. This time I’m in a different formation, and whose variation on “No justice! No jeeps! (No fords, no trucks, no nothing!)” encourages the dozen people I’m standing with.

As an IWW I am excited to see the militancy of these workers. Spurred by Shawn Fain’s bravado, these workers are eager. The mode of the strike is particularly interesting. I think we can learn a lot from watching this unfold; this is a patient strategy. In 2019 the UAW went on strike for forty days, and this will likely be longer. The Union targeted three different shops, owned by three different brands, at once. This is reminiscent of our union’s goal, which is that all workers in one industry organize together, not separated by shop. Unfortunately the UAW does not organize all auto workers. Currently engineers are not eligible for membership, for example. This is a fantastic time to be a Wobbly.

I will continue to monitor the strike and help where I can. Fellow Workers, I encourage you to participate as well. To sign up for UAW updates, follow this link. The bosses can’t scare us now. Solidarity!

-Zach

Note: As of September 22, 2023 38 additional Stellantis and GM plants went on strike. As of October 8, 2023, General Motors has made a 6th offer to the UAW, but it does not include the traditional pensions reinstated, nor the Cost-of-Living Adjustments lost in 2009, nor several other demands. Notably, it would include electric vehicle battery manufacturing workers in the master agreement.

Detroit GMB Participates in Hydrate Detroit May Day Event

On May 1, 2022, Hydrate Detroit and MIMAC (Michigan Mutual Aid Coalition) hosted a May Day event under the pavilion in Dueweke Park in Detroit. PSL, Fight For $15, and the Detroit General Membership Branch of the IWW also atteneded and participated in the event. The Detroit GMB helped fund the event by giving funds for food and drink, and the AgitProp committee tabled at the event. Free food was given out to try and draw in the public.

The Agit Prop committee talked about the IWW with attendees of the event. The committee sold buttons for a dollar and handed out copies of “Think It Over: An Introduction to the IWW”. Later in the evening, a member of the Detroit GMB branch appeared on a radio show to talk about the IWW.

Detroit wobs show solidarity with Windsor auto workers strike blockade

This January, members of the Detroit IWW traveled to the North American headquarters of Fiat Chrysler Automobiles (FCA) in Auburn Hills to show solidarity with striking auto industry workers across the border in Windsor, Canada.

Members of Local 444 of Unifor, Canada’s largest private sector union, barricaded the Windsor Assembly Plant on Jan. 5 as part of a labor dispute involving workers who drive completed minivans out of the factory, which is owned by Stellantis, a subsidiary of FCA. The strike began after 60 drivers who had been working there for Auto Warehousing Co. learned their jobs had been eliminated when Stellantis signed a deal with Motipark, another driver management company represented by the Teamsters, to take over the plants driving duties.

When that new contract took effect on Jan. 1, Motipark refused to take on any of the former drivers as employees. In response, Unifor argued they had successor rights for the driving work, meaning that the previously employed drivers should have kept their jobs and benefits. Looking at the two companies rates, it’s not hard to see why Stellantis might have been motivated to renegotiate its driving contracts; Motipark pays starting drivers $17.77 per hour, while Auto Warehousing Co. employees were paid between $20 and $24 per hour, according to Unifor Local 444. Aware of the dynamics of this situation, drivers barricaded the plant, which prevented new minivans from leaving the plant and created economic pressure for a settlement.

Upset with Stellantis and Motipark’s treatment of the drivers, 7 Detroit wobblies journeyed out Auburn Hills on Jan. 8 with banner reading: “Stand with Unifor 444,” in an effort to raise awareness about the labor struggle.

“We went there to do a banner drop, so we could show support and signal to Fiat Chrysler and to other people in the United States that we’re sympathetic to these workers,” says Nathan Reiber, Branch Secretary Treasurer of the Detroit IWW. “They had the right to continue working in that factory!”

The blockade finally came to an end on Jan. 19, when Unifor announced a deal restoring the drivers jobs at the plant, showing once again that direct action does get the goods!